Some shooters love lots of recoil and big slugs, if that’s you, it may be time to get a .50-caliber rifle.

Big-bore hunting rifles have a unique allure, as more often than not they’re associated with hunting dangerous game, especially African dangerous game. And where I’ve been quoted as saying—from the perspective of the visiting client—that I prefer my cartridges to start with a “4,” a good number of African Professional Hunters cock an eyebrow at me, and tell me they want their cartridges to start with a “5.”

Those rifle cartridges in the .50-caliber range are serious stopping cartridges, launching heavy bullets and generating heavy recoil. For ending a conflict with the largest animals on Earth, the .500s are great tools … if the shooter can handle the bone-crushing recoil.

Now, not all .50-caliber rifles are created equal—technically a .50-caliber Hawken muzzleloader fits the bill—and there are some of the smaller rifle cases that do launch .50-caliber projectiles, but are light-for-caliber. The .500 Linebaugh is available in the Big Horn Armory Model 89 lever-action, and the .50 Beowulf surely shines in the AR-platform, but both of these use lighter bullets than are needed for truly dangerous game. I feel that for this caliber of cartridge, a bullet of 500 grains minimum is needed to provide the proper Sectional Density for deep penetration on an animal that can stomp you into jelly.

The .500 Nitro Express

Starting with the oldest of the lot, the .500 Nitro Express dates back to the late 19th century. Based on the .500 Blackpowder Express, the British firm of Westley Richards was responsible for converting the cartridge to smokeless powder in 1890. The .500 Nitro Express is a rimmed cartridge, designed for use in the single-shot and double rifles, using a bullet of 0.510-inch diameter, in a straight-walled case measuring exactly 3 inches, with an overall length of 3.75 inches.

The large rim of the .500 Nitro Express—measuring 0.655 inch—allows for proper headspacing and positive extraction, even in the heat of the tropics. This was a very important design feature when the .500 Nitro Express made the transition from blackpowder to smokeless powder, as the vast majority of the rifles of this caliber were destined for India and Tropical Africa, and the Cordite used to fuel the cartridge was very sensitive to temperature fluctuations. A voluminous cartridge with a good, strong rim made a world of difference in the late 1800s.

The .500 Nitro Express is offered with one bullet weight—570 grains—as that’s the weight used to regulate the double rifles. At the standard muzzle velocity of 2,150 fps, that bullet will generate 5,850 foot-pounds of energy at the muzzle; couple that with the frontal diameter of the .500 NE and you’ve got a great stopping rifle. In a double rifle weighing between 11 and 12 pounds, the recoil of the .500 Nitro Express is surprisingly manageable.

In fact, owning and hunting with a .470 NE, I actually find the recoil speed and overall level of the .500 NE to be more pleasant than my .470. Where the .470 generated just over 69 foot-pounds of recoil energy, the .500 generates 75½ foot-pounds, but I’ve always found the speed of the .500s recoil to be slower, and therefore the perceived recoil to be less. While the .470 Nitro Express remains the most popular choice, with the widest variety of factory ammunition, many professional hunters still prefer the .500 NE for its heavier bullet weight and stopping power.

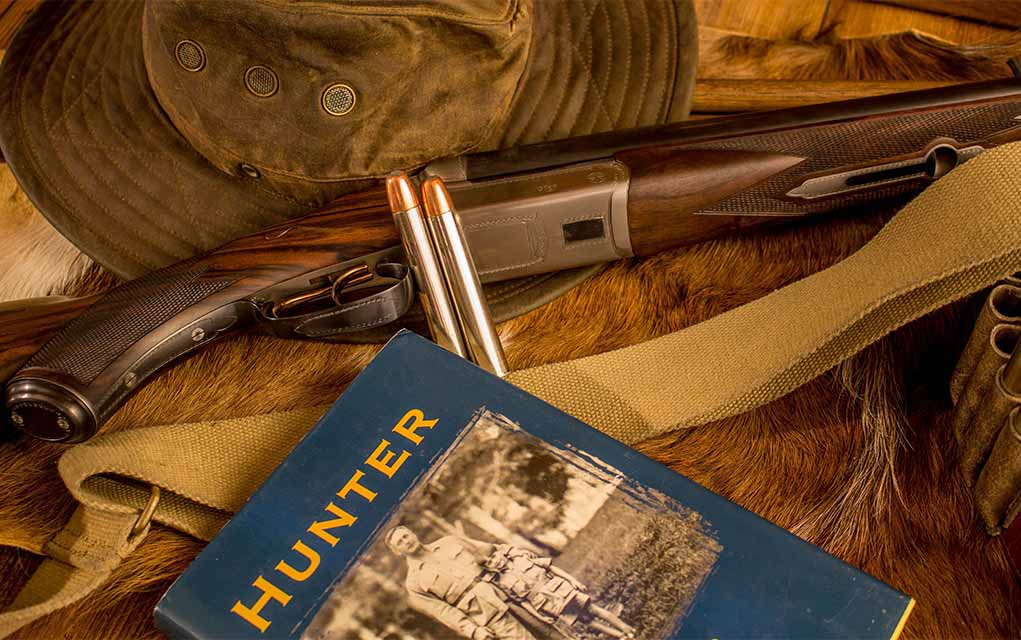

Historically, folks like John A. Hunter, Sten Cedergren, Gordon Cundill and Glen Cottar put the .500 NE to good use. (Hunter’s .500 Boswell rifle did serious work along the Lunatic Line, taking a huge number of rhino for the Uganda Railway Company—I’ve had the privilege of shooting this rifle.) In modern times, Professional Hunters (and personal friends) Brian van Blerk, Peter Dafner and Jofie Lamprecht all rely on a .500 Nitro Express in a Heym double rifle. Good ammunition is available from Hornady, Federal and Norma, and component bullets are readily available to those who handload their ammunition.

The .505 Gibbs

“Macomber did not know how the lion had felt before he started his rush, nor during it when the unbelievable smash of the .505 had hit him.” -Ernest Hemingway, The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber.

George Gibbs of Bristol designed the .505 Gibbs in 1911, using a bullet of nominal diameter, housed in a case measuring 3.150 inches long, with an overall cartridge length of 3.850 inches. The .505 is a rimless design, using a 37-degree, 40-minute shoulder for headspacing purposes, making the cartridge a perfect candidate for the bolt-action repeating rifles. Where the double rifles of the era were certainly very fast for a second shot, a bolt-action repeater is faster for the third shot. The .505 was released among some of our most revered safari cartridges, what with the .416 Rigby coming on the scene the same year, and the .375 H&H Magnum just a year later, and made a serious choice for those pursuing the big game species of Africa and India.

The initial load for the .505 Gibbs used a 525-grain bullet at a muzzle velocity of 2,300 fps, generating over 6,100 foot-pounds of energy at the business end of the barrel. Again, we have a cartridge originally fueled by the rather-volatile Cordite, and the sheer size of the Gibbs case shows the efforts to keep pressures low, in order to guarantee extraction in the heat of the tropics. Recoil isn’t for the faint of heart, as the .505 Gibbs will generate over 85 foot-pounds of recoil energy, depending upon the weight of the rifle. Projectiles as heavy as 600 grains are loaded in factory ammunition for the .505 Gibbs, and while these big slugs are quite effective on buffalo, elephant, hippo and the like, they do require both training and practice to shoot effectively.

My good friend and hunting partner Mike McNulty has the first of the new Heym Express rifles in .505 Gibbs to roll out of the shop, and we’ve done some extensive load development for it. Using Reloder 15 (which develops the same velocities with a lighter powder charge) and a Kynoch foam wad to keep the powder column in place, we can mitigate some of that recoil without losing performance. McNulty has taken buffalo and elephant, plus a number of plains game species, in Zimbabwe over the course of a few safaris, and that rifle is as sound a choice for dangerous game as you could make, providing you can handle that level of recoil.

Historically, the .505 Gibbs has seen considerable field action in the hands of PHs Barry Duckworth, Kevin “Doctari” Robertson and John Oosthuizen, as well as serving as the fictional Robert Wilson in Hemingway’s Macomber. Ammunition is available from Norma (though some sites indicate it has been discontinued) and from Nosler, though if you are serious about a Gibbs, I highly recommend you learn to handload your ammunition.

The .500 Jeffery

Here’s the youngest of the half-bores designed for safari work, born in Germany around 1920, and originally known as the 12.7×70 Schuler, or in some instances, the .500 Schuler. It was picked up—and anglicized—by the prestigious firm of W. J. Jeffery and offered as a true big bore cartridge designed to fit in a standard 98 Mauser action.

To do this, the .500 Jeffery has a rebated rim, measuring 0.575 inch in diameter and a case measuring 2.75 inches long; the cartridge overall length measures 3.46 inches. The slight 12-degree, 37-minute shoulder handles the headspacing duties and is a big factor in the way a .500 Jeffery feeds, but more about that in just a second. The .500 Jeffery uses the same .510-inch diameter projectiles as the .500 Nitro Express, with the original load using a 535-grain bullet at a muzzle velocity of 2,400 fps, to give 6,800 foot-pounds of energy at the muzzle. This was the most powerful shoulder-fired cartridge until the .460 Weatherby Magnum came along to take that title.

Using well over 100 grains of powder, the .500 Jeffery is assuredly a dangerous game cartridge if ever there was one. And as modern loads exceed those of the .505 Gibbs, in a 10- to 11-pound rifle, the recoil energy can approach or exceed 90 to 100 foot-pounds, so you’re really going to want to make sure the stock fits you well. Though the 535-grain bullets were originally loaded, many companies have offered the 570-grain bullets usually produced for the .500 NE at a muzzle velocity of 2,150 fps, the same as the .500 Nitro Express. For the handloader, component bullets are available from Barnes, Cutting Edge Bullets, Swift and Hornady.

Though discontinued, a number of CZ550 rifles are still on the market, chambered in .500 Jeffery. Factory loaded ammunition is becoming a problem though, as Norma has apparently discontinued both ammunition and component brass, and they were a big supplier. Buffalo Bore lists loaded ammunition, loaded with solid (non-expanding) projectiles.

Oh, that feeding issue I alluded to earlier? A common issue with many .500 Jeffery bolt-action rifles is a magazine follower that doesn’t stay parallel with the barrel, as cartridges are loaded into the chamber. If that follower develops a nose-up attitude, the bottom edge of the bolt can ride over the cartridge’s rebated rim, causing a failure-to-feed situation, resulting in a hairy predicament if a wounded or charging game animal is on the other end of the line.

If you plan on taking your .500 Jeffery in pursuit of dangerous game, I highly recommend you spend considerable time making sure your rifle will reliably feed in all sorts of situations; it’s often the last cartridge in the magazine that shows the most potential for this phenomenon.

In the heyday of safari, the most popular user of the .500 Jeffery was Crawford Fletcher Jamison, who had one of only 23 Jeffery’s rifles. Equipped with a 26-inch barrel and a very long length of pull, I had the honor of shooting that rifle, which seems to deliver less perceived recoil than do modern rifles. In modern times, my friends Jay Leyendecker, Mike Fell and the late Dudley Rogers have all relied on the .500 Jeffery to keep their clients on one piece while on safari.

The .50 BMG

I’m often asked by prospective hunters of dangerous game exactly why, if these beasts are so tough, hunters don’t ever use the .50 BMG for that purpose. The short answer is that the rifles chambered for the Big .50 simply aren’t designed for stalking, and that’s the preferred method of hunting Cape buffalo, elephant and the few rhino that are still sport hunted each year.

Toting a 30-pound rifle in the African bushveld simply isn’t practical—I know just carrying my 12-pound .470 NE Heym double or 10-pound .404 Jeffery bolt gun on a sweltering day under the African sun is tough enough, let alone almost three times that weight. The ballistics are certainly sound, with the Browning design launching a 650- to 750-grain bullet of 0.510-inch diameter to a muzzle velocity of somewhere between 2,800 to 3,000 fps, generating over 13,000 foot-pounds of energy.

However, I think that no matter how many gunbearers one employed, carrying a .50 BMG on safari just doesn’t make practical sense.

Editor’s Note: This article originally appeared in the May 2024 issue of Gun Digest the Magazine.

More .50-Caliber Stuff:

Next Step: Get your FREE Printable Target Pack

Enhance your shooting precision with our 62 MOA Targets, perfect for rifles and handguns. Crafted in collaboration with Storm Tactical for accuracy and versatility.

Subscribe to the Gun Digest email newsletter and get your downloadable target pack sent straight to your inbox. Stay updated with the latest firearms info in the industry.