(Psst: The FTC wants me to remind you that this website contains affiliate links. That means if you make a purchase from a link you click on, I might receive a small commission. This does not increase the price you’ll pay for that item nor does it decrease the awesomeness of the item. ~ Daisy)

Important news: growing your own food is bad for the climate. Leave it to the experts if you love the planet.

Ever notice how we’re not supposed to respond to any of our current crises by learning and bettering ourselves? We weren’t supposed to confront Covid with the conviction to improve our health through diet and exercise. We were just supposed to follow CDC guidelines. We weren’t supposed to ask difficult questions about how war in Ukraine could have been avoided. We were just supposed to accept whatever legacy media told us.

And now it turns out that we are not supposed to address environmental concerns by shortening our food chains and lessening our reliance on complex transportation systems.

Didn’t you hear? Growing your own food is bad for the climate.

Grow flowers, not food.

In what might be the stupidest article I’ve ever read, a new study from the University of Michigan announced that growing your own food in urban settings can emit five times as much carbon as those grown in “conventional” settings. Scientists say that the emissions don’t come from the vegetables themselves but from infrastructure in the form of sheds and raised beds. They suggest that, for those who must garden, growing high-carbon input foods like tomatoes and asparagus is less harmful. Those foods take a lot of carbon regardless of where they’re produced. Asparagus, in particular, is often flown into the U.S. from around the world.

The article’s suggestions to “grow green” were to:

- Grow tomatoes

- Grow asparagus

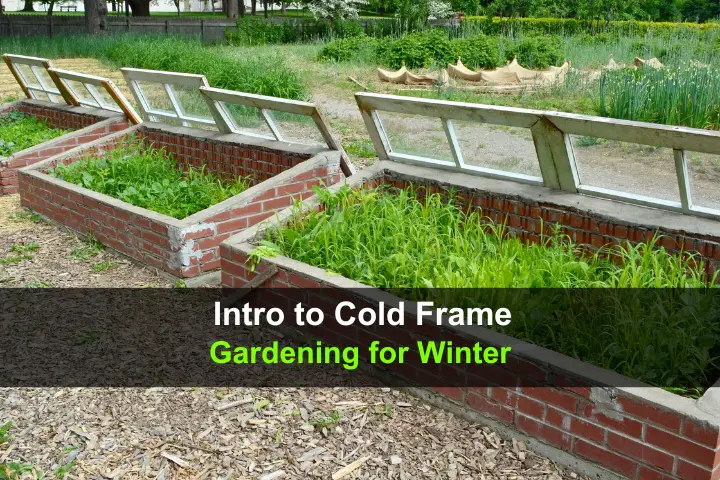

- Use recycled wood and building materials

- Repair, don’t replace, aging sheds and garden beds

- Grow 90% flowers, not foods, to offset emissions with “social benefits”

I do grow tomatoes and asparagus because I like them, not because of “climate change.” My shed is over twenty years old, as I imagine a lot of sheds are. Who would put up a new shed every year?

This article does not even pretend to address the carbon offset by producing your own food rather than getting it transported into cities. I’ve been fortunate enough to live in a few agricultural valleys where I can get many of my basics (carrots, potatoes, cabbage, onions) grown within a 50-mile radius.

However, I’ve also spent time in bigger metropolitan areas, where you just can’t. The Chicago metro area, for example, extends for dozens of miles in every direction from the lake. There are some really nice farmers’ markets in the city and the suburbs, but in general, your food in Chicago is coming from a significant distance. Any way you can shorten that will be beneficial in terms of carbon offsets.

And this article doesn’t even pretend to quantify the myriad other benefits of gardening, benefits that also reduce costs to the environment.

Rebuttal: Growing your own food can actually benefit the environment.

I began gardening as a young at-home mom with multiple children. We lived in a suburban area. We had to drive almost everywhere. And because we were in Texas, with its limited publicly-owned lands, if I wanted to get out of the house, that meant we were spending money.

My family was young, energetic, and trying to make ends meet on a single income. Our suburban garden paid for itself in terms of money saved at the grocery store within four years. However, I realized that the project was “worth it” almost immediately. Time spent playing in the garden was time I did not have to spend driving around town to various playgrounds or children’s outings. As the kids grew older, the garden turned into an endless science project that I didn’t have to pay for. Our continually fed and used compost pile kept food out of landfills. This at-home entertainment allowed us to reduce consumption without reducing our quality of life.

And the money/kid entertainment value is only the beginning. Gardens add beauty and uniqueness to suburban lots. I can’t think of many sights more depressing than row upon row of cookie-cutter houses with cookie-cutter yards. Think of the beginning of Harry Potter, when they introduce the Dursleys. Gen Xers can hearken back to the music video for Rush’s “Subdivisions.”

Gardens change that. A lot of people have to live in cookie-cutter homes for one reason or another. A skilled gardener can make any lot interesting and unique.

Mental health benefits of growing your own food

This is not just some luxury. Access to natural beauty has a whole host of benefits for mental health. Common sense should reveal this to most of us. If you don’t want to take my word for it, read clinical psychologist-turned-neural imaging specialist Dr. Iain McGilchrist’s books The Master and His Emissary for a deep dive into the science behind the stress-relieving power of natural beauty.

Living in a pleasant environment means less of an urge to go away all the time, less driving to tourist attractions, less money spent trying to kill the time because you can’t really relax at home. A pleasant home reduces the need for other kinds of consumption, and a garden can be part of that.

Gardening has other mental health benefits as well. As a nation in the midst of a mental health crisis, we ought to be paying attention. As any skill develops, failures occur. If you are gardening with children, they will learn that sometimes seeds don’t sprout. Sometimes, late frosts kill things. Sometimes, hailstorms destroy your lovingly tended plants. If children grow up watching their parents try, fail, and then try again, they grow up less afraid of making mistakes. This builds resilience.

For those who stick it out, the ability to grow a portion of your own food builds confidence. Any skill, once mastered, is good for your self-image. But growing food, in particular, gives you a sense of security and a sense of connection with past generations. It connects you with your place; you can’t grow the same varieties in Chicago as you can in Houston. Gardening forces you to acquaint yourself with your environment. In our highly mobile society, gardening can give us a sense of stability.

All of these are facets of an experience that can make us happier, healthier, more confident, and less reliant on the global trade network. Again, gardening is a way to reduce consumption (better for the environment) without reducing quality of life (better for us).

Why take the fun out of something so wholesome?

I don’t think this is just about money. Yes, I think there is a push to consolidate the food supply, as we’ve discussed before. The fight over independent food production seems to be getting more important every day. In this past week, the European farmers’ protests have heated up enough that Belgian police began firing rubber bullets and water cannons at the protesters.

But I think this aspect, in particular, the drive to make people feel guilty about an enjoyable hobby, has to do with demoralization.

One of the lines within the articles is,”. . .vegetables were 5.8 times better for the environment when left to the professionals.”

“Left to the professionals.” Don’t we hear that often enough?

I mean, sure, some things need to be left to professionals. I don’t want a hobbyist resetting a broken arm.

But food produced by yourself is often better than what you get from the store, as any experienced gardener knows. It’s fresh and has never spent a day in the back of a truck. The only objective standard by which “conventionally” grown produce is typically better is usually the price tag. Living on poor-quality food is demoralizing, and so is the thought that we can’t take any steps to better our circumstances.

Forces within our society are trying to keep us stupid, helpless, and compliant. This becomes more obvious to me every year. We are constantly being seduced by the siren song of convenience, ease, and how we should just leave every aspect of our lives “to the professionals.”

No.

Professionals have their place, but competent hobbyists have their place, too, and there are a lot of areas in your own life in which no, actually, you don’t need a college degree and specialized training. Growing your own vegetables is one of them.

I’m not saying everyone has to get out and garden. But if you are looking for projects, if you’re feeling the itch, don’t let the bastards get you down. Learning to grow some of your own food is a wonderful experience.

What are your thoughts?

Do you think there’s any merit to the theory of growing your own food being bad for the environment? Why do you think these theorists want to reduce self-reliance? Share your thoughts in the comments section.

About Marie Hawthorne

A lover of novels and cultivator of superb apple pie recipes, Marie spends her free time writing about the world around her.