A complete guide to finding the best rimfire riflescope for your needs.

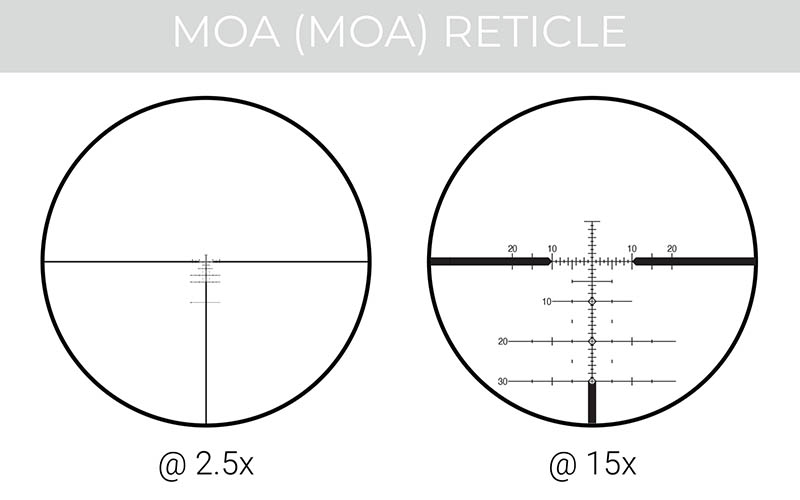

The biggest hurdle for new shooters interested in precision rimfire always seems to involve optics. There are turrets, and parallax, and complicated reticles and debates over minutes-of-angle (MOA) versus milliradians (MILs). Coming from a hunting background or another discipline like silhouette where you held the crosshairs on the target, a more complicated aiming system can feel overwhelming.

It does not help that “rimfire” plus “scope” just meant crappy for the longest time. The glass was inferior. The adjustments were spotty. Drop one or get it wet, and the scope was toast. Here’s the thing: You don’t need a “rimfire” scope for a “rimfire” rifle. Whether you need an optic for competition or hunting, most quality centerfire scopes will do the job, yet some are better suited for small-bore work than others.

Shooters define riflescopes by tube diameter. One inch is the classic and most common diameter and is still great for small-game rigs. 30mm is the new standard for tactical and match shooting. 34mm is the super-sized big brother and best-suited for extreme long-range work. There are now even 36mm beasts like the Zero Compromise optics and 40mm digital range-finding scopes like the Swarovski dS Gen II. The fatter the scope, the more room for elevation adjustment, thus the more you can spin that turret for a dead-on hold way downrange.

Consider this example. The 30mm Vortex Diamondback Tactical 6-24×50 FFP—a popular base-class NRL22 optic—has 19 MRAD or MILs max elevation adjustment. That means if you zero the scope at the bottommost point, you can compensate for 19 MILs of bullet drop. With match-speed .22 LR and the scope zeroed at 50 yards, that’s enough reach to connect to about 350 yards. The Vortex Strike Eagle 5-25×56 FFP with a 34mm tube brings 31 MILs of max elevation adjustment. That equates roughly to 470 yards of possibility. Keep in mind, this is theoretical as it’s difficult to zero scopes at their lowest elevation setting, and the equation changes with tapered rails and scope rings, as we’ll soon see. This example demonstrates the leap in max range one gets with a 34mm tube over 30mm. Compared to a classic 1-inch scope, the difference is planetary.

MOA Vs. MILs

You make riflescope elevation and windage adjustments in MOA or MILs. To make things confusing, MILs are often also abbreviated as MRAD. They are the same thing for practical purposes. MOA and MILs or MRAD are angular measurements over a given distance rather than a linear distance. With a linear measurement, an inch is an inch. With angular, the value changes based on distance. I visualize this like a laser beam shooting directly from my barrel’s bore through targets from 100 to 1,000 yards. If I change the degree of that beam to mark a spot 1 foot over the target at 100 yards, it’ll put the beam dozens of feet over the target at 1,000 yards. MOA and MILs are units that measure how much I’m moving that laser beam at the rifle to determine where it will hit at various targets downrange.

One MOA equals 1.047 inches at 100 yards and 10.47 inches at 1,000 yards—not 1 inch and 10 inches, as many wrongly believe. (This difference of 0.047 inch matters at distance, especially with rimfire where the elevation drops quickly.) One MIL equals 3.6 inches at 100 yards, which equates to 36 inches or 1 yard at 1,000 yards. Scope adjustments in MOA are usually 1/4 MOA per “click.” MILs are often .1 or .2 MILs per click or less. Some wrongly conclude that MOA has more subtle adjustment than MILs, but it’s a toss-up. A typical one-click adjustment in MOA is 0.25 inch at 100 yards, whereas MILs can go as low as 0.18 inch at 100.

You can convert an MOA value to MILs by dividing it by 3.43, a MIL to MOA by multiplying it by 3.43.

So, which is better?

Neither system is inherently better or worse. A shooter with experience who understands one approach over the other should stick with what they know. But new shooters, or shooters who want to dive down the long-range rabbit hole, should lean toward MILs. MILs are the standard measure for the U.S. Military and are used worldwide, unlike MOA that’s only used in a handful of civilian markets—and is rapidly going out of style. Reasons for that are multiple, but at its root, if you learn both systems, you’ll see that computing MILs quickly in your head is generally faster than MOA. MILs “click,” at least for me, in a way that MOA struggles, mainly because in MIL calculations, it’s possible a lot of times to move the decimal place.

To learn the precision shooting language of MILs, I strongly recommend Ryan Cleckner’s Long Range Shooting Handbook: The Complete Beginner’s Guide to Precision Rifle Shooting.

MILs is the language of most precision shooters. You’re more likely to talk shop and get help in MILs at a match than MOA. Also, when using ballistics programs to solve long-range shooting problems, MOA can create issues. Some optics manufacturers have incorrectly set MOA on their scopes for 1 inch at 100 yards instead of 1.047 inches. If your ballistics program is calculating based on 1 MOA equaling 1.047 inches, but your optic is adjusting 1 MOA equals 1 inch, you could miss the target.

That’s especially true in long-distance rimfire shooting, where you need to make significant scope adjustments at not-so-big distances. A 0.047-inch error can compound very quickly in .22 LR. It’s also a challenge to figure out if an MOA riflescope uses 1.047- or 1-inch adjustments. Nikon always used 1.047 for MOA, but Vortex uses 1 inch. If you go MOA over MILs in precision optics, you may have to call customer service to get the numbers straight. If, as I did, you shoot both Nikon and Vortex MOA optics, you need to make sure you change the MOA value in your ballistics program to get accurate results for each rifle system.

MILs, being universal, avoid all this rigmarole.

With scope size determined and the MOA versus MILs argument decided, there are five factors to consider when settling on a precision rimfire riflescope: parallax, focal plane, reticle design, turrets and magnification power. Let’s look at them:

Adjustable Parallax

If you’ve ever seen the reticle (crosshairs) of your scope float or come in and out of focus while on target, you’ve probably noticed the phenomenon of parallax. The reticle and the target are no longer on the same focal plane within the scope’s main tube. The difference between focal planes becomes exaggerated at extremely close and far target distances—decreasing accuracy and obscuring the reticle. Some scopes allow you to manually adjust for this and bring everything into focus at specified target distances, while others have fixed parallax at a specific range.

Most centerfire scopes with fixed parallax are factory-focused, around 150 to 175 yards—too far for typical rimfire applications. Manufacturers set fixed parallax rimfire riflescopes at 50 or 60 yards, which can work fine for small game hunting but make 20- or 25-yard shots—standard in many small-bore sports—a blurry mess. For any precision small-bore match scope and most hunting scenarios, I recommend an adjustable parallax down to at least 25 yards.

Most tactical-inspired and long-range centerfire scopes have a side knob for parallax adjustment, sometimes called “side focus.” Bench shooting target scopes often have the parallax control built into the objective bell, called “Adjustable Objective” or AO. Side controls are easier to run when jumping between near and far targets within the same shot string in a match. AO controls work fine when you have plenty of time. For match shooting, I highly recommend adjustable parallax via a side focus knob.

Focal Plane

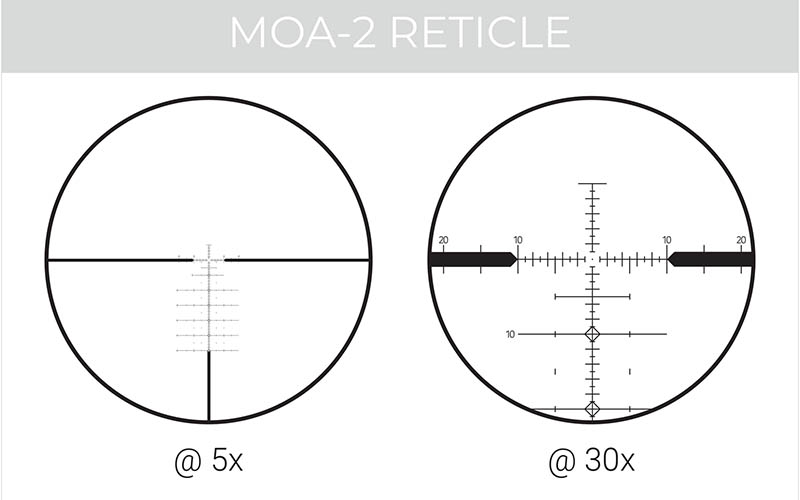

There are two locations within the tube where makers install the reticle. If the reticle goes in toward the objective lens (the front of the tube), that’s called first focal plane (FFP). If it goes in near the ocular lens or the back of the tube, that’s called second focal plane (SFP). When dialing up the magnification on a FFP scope, the reticle will grow larger. In SFP scopes, the reticle will appear the same size no matter the magnification. There are pros and cons to each.

Many long-range shooters and hunters have migrated to FFP scopes because reticle holdover values don’t change with the scope power. In other words, if every hash mark along the vertical stadia (the main crosshair line) represents 1 MOA at the lowest power, they still equal 1 MOA at the highest magnification. The second hash under the central crosshair equals 1 MOA drop at 4x power and 16x power. FFP scopes are a significant advantage in some precision matches where single-stage targets may be from 20 to 100 yards or beyond, and the shooter must change scope magnification and holdover within the shot string.

An FFP optic’s drawback is that the reticle can be small and hard to see at the power range’s low end. In my NRL22 matches, many older shooters struggle to see the FFP reticles when turned down to 4x and 6x or even 8x. FFP systems are not for older eyes. Hard-to-see reticles also don’t work well while hunting, where you might have to tease out a squirrel head in a tangle of branches and leaves. Fat, clear, stadia work much better.

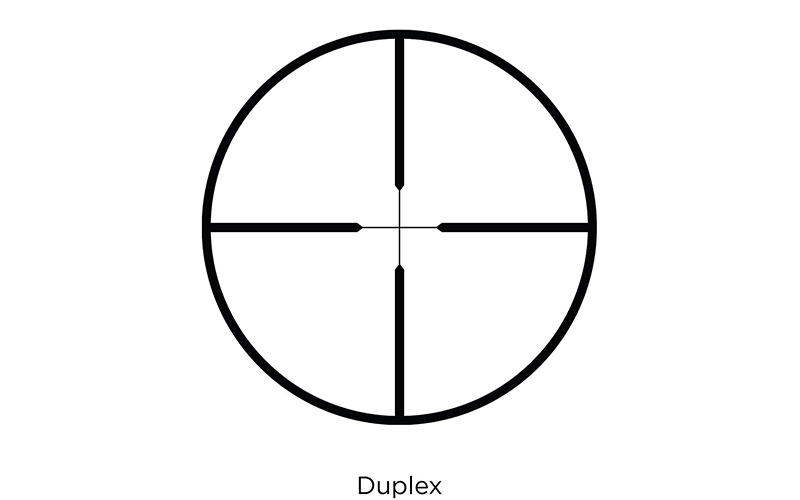

Second focal plane scopes work well in these situations, and old or bad eyes can usually find the mark quickly. The classic duplex reticle draws the eye to the center and makes for high-speed target acquisition. SFP scopes also tend to be less expensive than FFPs, but the former can cause trouble when you use the reticles for drop compensation.

Several years ago, I was on a pronghorn hunt in Wyoming. I had a .25-06 with me and tagged out on the first morning. A friend had long wanted a .25-06, and as we talked about it, I suggested he borrow my rifle to get his goat. Taped to the stock’s side was the bullet drop for that SFP reticle when at the full 16x power. My friend came back after that first day discouraged. He had missed a shot at 400 yards—sailing the bullet over the old buck’s back. The animal was grazing broadside. He had a steady rest and decades of Western hunting experience that made this shot—he thought—a layup. He had used my DOPE chart on the side of the stock, and when he shot, the scope was at 14x. At that magnification power, my chart was worthless. That’s a rare situation, but it goes to show how “off” a reticle can be within an SFP scope if you don’t pay careful attention to magnification. In the more likely event of moving fast through a competition stage, running different targets at different scope powers could be a real liability.

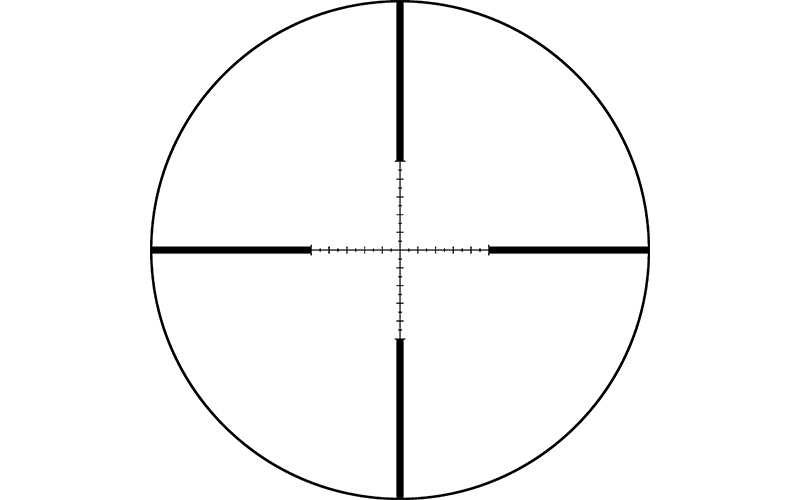

Reticle Design

In the last few years, no part of the riflescope has been designed and redesigned more than the reticle or aiming point. For hunting with laser-flat .17 caliber, it’s hard to beat a simple duplex crosshair. Developed in the 1960s by Leupold, the duplex uses four heavy crosshair lines that taper down to fine lines where they meet in the center. This design makes placing the crosshairs on a target fast, and it always provides a clean sight picture.

When shooting slow rimfire loads like .22 LR, bullet drop is more of an issue. For hunting work, .22 LR Ballistic Drop Compensating (BDC) reticles, like those in the now-discontinued Nikon Prostaff Rimfire series, can work very well. Tract Optics and Hawke Optics have picked up the slack, producing dedicated rimfire BDC scopes that are not junk like many “rimfire” scopes. BDC optics have reticles with hash marks tuned to either standard-velocity .22 LR, high-velocity .22 LR, or .17 HMR, indicating where the bullet will impact at longer ranges. It takes some trial and error to figure exactly where the hash marks and downrange impacts line up, but once you figure it out, it’s a fast and elegant solution for a hunting or plinking rifle.

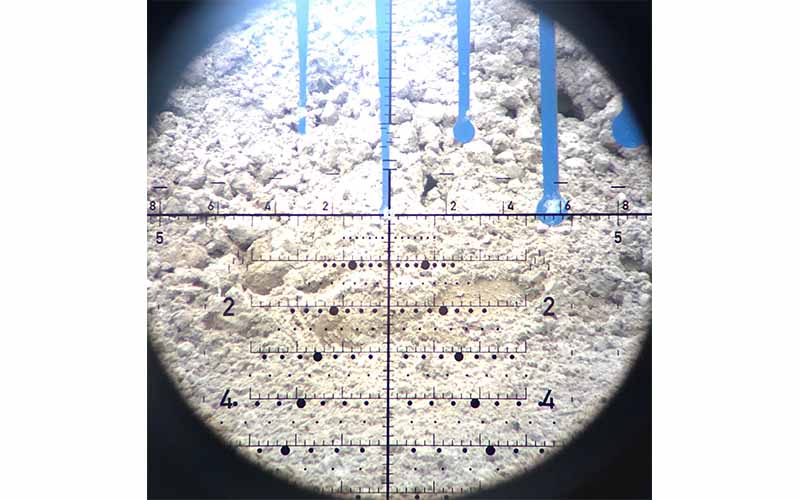

Competition reticles can quickly become complicated. Rather than hash marks indicating likely holdovers by caliber, each line may represent a certain number of MOA or MILs. The sub-tensions or white space between the hashes all have a set value, too. The finer these marks are, the more precise the measurement, theoretically. But too many marks can quickly clutter the sight picture, particularly for a shooter who has spent their life using a duplex. That is especially the case with FFP scopes on low magnification, where a complicated reticle can look like smudged ink. But, when lying prone 100 yards or more from your target with match .22 LR ammo that drops like a brick, all those hash marks become very handy.

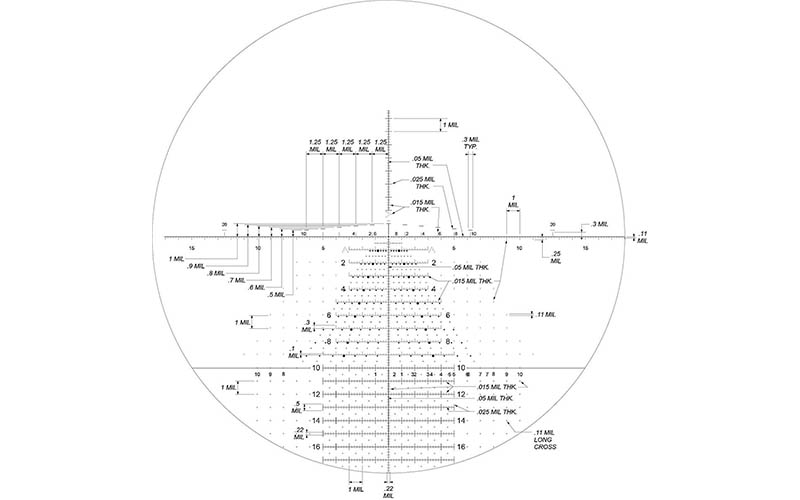

Different optics companies run various reticles, but there are a few standards. The Horus H59 started a revolution of “Christmas tree-style” reticles and quickly became the standard for many elite marksmen. Below the centerline is a grid laid out in 0.2-MIL increments that make for exact drop calculations and fast follow-up shots. It’s clear to see where the first shot landed, then hold that spot in the reticle for the second shot. At first blush, a system like the H59 and the many similar reticles it spawned can look like a complex geometry problem but spend some time with them on the range, and it comes together quickly. Like understanding MILs, these reticles make good sense with a little time spent behind the trigger.

Turrets

For the most part, there are two kinds of turrets available on riflescopes. You can get either exposed turrets, which allow for manual adjustments in the field, or capped turrets usually adjusted once when zeroing a rifle, then left alone. Most precision shooters use adjustable turrets, which allow you to dial-in precision shots for a given range.

For a .22 LR with a 50-yard zero, the crosshair center is still an accurate hold from 20 to 60 yards or more, depending on ammo velocity. Push out beyond 60 or 70 yards, and the shooter has a decision to make: Use the hash marks on the reticle to hold over the target, or spin up the turret and hold the center. In a PRS-style rimfire match, if the stage involves shooting a close target, at say 30 yards, then jumping to a 100-yard plate, most shooters use the reticle. If target distances are fixed at 65 yards or more, dialing the turrets is a more elegant solution. However, for extended-distance rimfire shooting, like the developing sport of Extreme Long Range rimfire—or when clipping varmints across the plains—adjustable turrets are necessary.

I’m partial to turrets that lock. To spin them, you pull up on the turret, which lets it click free. Push the turret down, and it won’t move on you. Many less expensive tactical scopes don’t have locking turrets, which strikes me as a risk while afield.

When you’re in the woods chasing squirrels or rabbits, all turrets tend to just get in the way. Most of the shots taken at small game are inside 60 yards, anyway. I’ve played with optics with complicated reticles and turrets on hunting rifles and have migrated away from them. Duplex reticles and capped adjustments work for me in the hunting woods, complicated reticles and big locking turrets for competition rigs.

Magnification Power

Magnification is useful, and it’s the first thing many people consider when buying optics, but it’s probably the least important feature when hunting or competing in a rimfire match. Sure, when shooting from a rock-solid rest at a tiny target 1,000 yards away, 35x magnification is handy, but in most cases, that’s not the situation.

Match shooting like in NRL or PRS is often done from compromised and unsteady shooting positions at reasonable-for-caliber distances. The targets are rarely less than 1 MOA in size. Significant magnification can amplify wobbles and shakes and hurt the shot from unsteady rests. Unless you’re going long on a varmint or ground squirrel hunt, magnification is even less critical when hunting small game. It’s hard to beat 3-9x or 4-16x for a hunting setup. One of the killing-est bushy tail hunters I know spent most of his career behind a fixed 4x scope. Many run larger scopes with power ranges from 4x to 5x on the low end to 25x or 35x on the high end for match shooting. But all those shooters will tell you most of the time they live in the middle band of that power range. A superior-quality scope with less power than you think you need is often a better call than a lower-quality scope with a massive high-end zoom.

Recommended Rimfire Riflescopes

What is the best optic for your rifle? That’s a hard question to answer and highly dependent on your end-use. As mentioned, I prefer MILs over MOA. I like 1-inch optics without turrets for hunting rimfires because they’re lighter and look better on a sporter rifle. For varmint hunting and traditional 100-yard NRL22 competition, I lean toward 30mm optics with locking turrets for the added adjustment and security in rough and tumble stages. For ELR, I like 34mm. Considering these features, I then look at the price. As a general rule, I want the MSRP of the riflescope to match or exceed the MSRP of the rifle. In many shooting situations, especially NRL22, the optic is more important than the gun. Repeat: The optic is more important than the gun. That’s because even low-end factory rifles have enough raw accuracy to be competitive at NRL22—or snipe a squirrel at 100 yards—but you cannot say the same about low-end optics.

Some optic manufacturers are ahead of others when it comes to precision. Look at the gear survey from the 2020 NRL22 National Match, and you’ll get an idea of who is leading the charge. Of the 68 shooters surveyed, 30 chose Vortex, 11 Athlon and 9 ran Nightforce. If you consider high-end optics (read: expensive), you could add Kahles, US Optics, Zero Compromise, and Trijicon, to that Nightforce in a “money is no object” class of the best riflescopes.

What follows is a roundup of some of the better general interest match and hunting optics, whatever the budget. I’ve personally shot all these on rimfire rifles and will vouch for them. Optics makers introduce new scopes every year that push the performance level, so this list is by no means exclusive. There are some great scopes not included here. A savvy buyer looking for a competition optic will track what the pros are using in their shooting discipline of choice, such as through the posted National Rifle League gear surveys. You can also follow the very excellent Precision Rifle Blog or track the various benchrest or other shooting organizations in which they compete—most publish extensive winning gear lists.

Editor’s Note: This article is an excerpt of Gun Digest’s Rimfire Revolution: A Complete Guide to Modern .22 Rifles.

More Riflescopes:

Next Step: Get your FREE Printable Target Pack

Enhance your shooting precision with our 62 MOA Targets, perfect for rifles and handguns. Crafted in collaboration with Storm Tactical for accuracy and versatility.

Subscribe to the Gun Digest email newsletter and get your downloadable target pack sent straight to your inbox. Stay updated with the latest firearms info in the industry.