This excerpt from The Ballistics Handbook discusses barrels, twist rates and how they influence bullet flight from muzzle to target.

The barrel is the rifle’s delivery system, the steel guidance mechanism that sends the projectile spinning toward the target. Barrel technology has come leaps and bounds in the last century, to the point where the accuracy has become both highly predictable, as well as repeatable. It’s important to know how barrels work in order to better understand how a bullet will perform within its confines.

The Throat

Starting at the breech end, your barrel has three or four main parts, depending on the type of firearm. For rifles, as well as semi-automatic pistols, there is a chamber, throat or leade, and the rifling itself, all terminating at the crown. The chamber is a mirror image of the cartridge to be fired and is sealed by the breech bolt or block to ensure all the burning gas pushes things toward the muzzle end of the barrel. The throat, or leade, is the area between the chamber of the barrel and the point where the rifling begins. The length of the throat can vary greatly, from less than 1/16 inch, to as much as ½ inch, depending on the cartridge and manufacturer. The throat is exposed to burning powder and hot gas, and when shooting a high-velocity cartridge is often the first part of the firearm to show wear and erosion. Some of the fastest cartridges, like the .300 Remington Ultra Magnum and .264 Winchester Magnum, can show throat wear in as little as 1,500 rounds. I make a conscious effort not to heat my barrels excessively, to help keep wear and tear to a minimum. Some companies (Weatherby for example) purposely extend the throat of their barrels to give room for the bullet to jump. This is known as free-bore, and can help increase accuracy. You never want a modern cartridge to have the projectile touching the rifling; dangerous pressures can easily develop. At the end of the throat, the rifling begins.

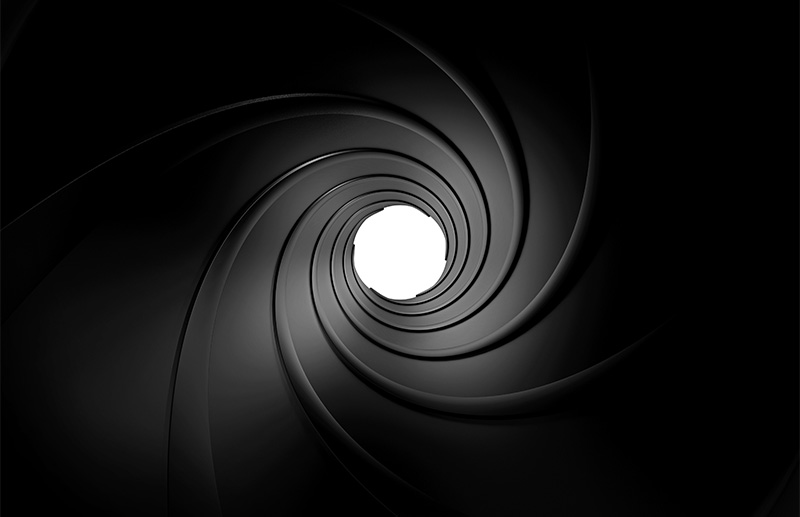

Rifling

Rifling is the set of twisted ridges you’ll see when you look down the bore of the firearm. It imparts a spin on the bullet, keeping it stable in flight. Those ridges, properly called lands, engrave their imprint into your bullet, and are machined at a smaller diameter than the bullet itself. The corresponding valleys, or grooves, are designed to be at caliber dimension to properly seal the gas and build pressure. The number of lands and grooves can vary, from the two-groove U.S. Army Springfield rifles of the early 20th century, to the Marlin MicroGroove barrel that used 16 or more, and all sorts in between. (Note: some handgun companies today employ polygonal rifling, which is a bit of a different geometry, yet works fine for their purposes.)

Almost all common barrels use a static twist rate, meaning that the grooves are cut in a specific manner to maintain a consistent spin on the bullet. When researching rifles, note the barrel specs listed as 1:10 or 1:7 twist rate. This is simply a means of telling you how fast or slow the barrel will cause the bullet to spin. The example twist rates given above work like this: a barrel with a 1:10 twist rate will have a bore in which the lands make a complete revolution in 10 inches of barrel (“1 in 10”), while the 1:7 barrel will make that same complete revolution in just 7 inches of barrel, therefore imparting more spin on the bullet. The higher the sectional density figure of a particular bullet (read that as a longer bullet), the faster it must be spun in order to maintain gyroscopic stability throughout its flight. While the numbers may be deceiving, a 1:10 barrel is called a slower twist than is 1:7, and with many of today’s bullets becoming longer and heavier for caliber, the fast twist rate barrels are becoming more desirable to take advantage of these bullets.

One of my favorite varmint rifles is a Ruger Model 77 MkII, chambered in .22-250 Remington. This big case is the old .250-3000 Savage necked down to hold .224-inch diameter bullets, and there is plenty of powder capacity to push the bullets to high velocity. However, because the .22-250 uses a relatively slow twist rate—either 1:12 or 1:14—the heaviest bullet I can use in this rifle is a 55-grain slug. While there are plenty of good, heavy bullets for hunting and/or target work available in this caliber right up to 80 grains and more, my rifle can’t stabilize them with that slower twist rate. My dad’s .223 Remington, with its 1:8 twist rate, can shoot most of the heavier designs without issue, even though it has much less case capacity. My .22-250 serves me well, and can really reach out and touch the coyotes and woodchucks, but I’d love to be able to utilize the longer bullets.

For years, I used a .308 Winchester exclusively as my big game rifle here in Upstate New York. I shot a .308 because Dad shot a .308, and we always discussed the reasons that we couldn’t use the heavy, 220-grain round-nosed slugs common in the .30-06 Springfield. He insisted it was a case capacity issue, but I found out that the .308 Winchester was originally released with a 1:12 twist, as opposed to the Springfield’s 1:10, so it couldn’t stabilize bullets heavier than 200 grains. (The .30-06 Springfield, normally supplying a 1:10 twist, can stabilize the heavy 220-grain bullets, but the .308 Winchester with a 1:12 cannot.) To prove my point, I borrowed a .308 Winchester with the faster twist rate, and loaded up some 220-grain pills. Much to my father’s chagrin, they worked just fine.

Here’s a chart of many common twist rates, from popular manufacturers. Of course, there may be some variations, but this should give you a good starting point.

Common Twist Rates for Rifle Calibers:

- .17 Mach II……………………………… 1:9

- .17 Hornady Magnum Rimfire…… 1:9

- .17 Winchester Super Magnum…. 1:9

- .17 Hornet ………………………………. 1:9

- .17 Remington…………………………. 1.9

- .204 Ruger …………………………….. 1:12

- .22 Long Rifle………………………… 1:16

- .22 Winchester Magnum Rimfire 1:16

- .22 Hornet …………………………….. 1:14

- .222 Remington…………………….. 1:14

- .223 Remington…… 1:7, 1:8, 1:9, 1:12

- .223 WSSM……………………………. 1:10

- .22 ARC…………………………………… 1:7

- .224 Valkyrie……………………………. 1:7

- .22-250 Remington…………. 1:12, 1:14

- .220 Swift……………………… 1:12, 1:14

- 6mm Remington/.244 Rem. 1:9, 1:12

- .243 Winchester…………………….. 1:10

- .243 WSSM……………………………. 1:10

- .240 Weatherby Magnum ………. 1:9.5

- 6 Norma BR …………………………….. 1:8

- 6mm ARC………………………………… 1:7

- 6mm Creedmoor…………….. 1:7.7, 1:8

- .25-’06 Remington………………….. 1:10

- .257 Roberts…………………. 1:9.5, 1:10

- .250/3000 Savage…………… 1:10, 1:14

- .25 WSSM……………………………… 1:10

- .257 Weatherby Magnum………. 1:9.5

- .260 Remington…………………. 1:8, 1:9

- 6.5 Grendel……………………………… 1:8

- 6.5 Creedmoor…………………………. 1:8

- 6.5×55 Swedish Mauser………….. 1:7.5

- 6.5-284 Norma…………………… 1:8, 1:9

- 6.5 PRC……………………………………. 1:8

- .264 Winchester Magnum…… 1:8, 1:9

- .26 Nosler……………………………….. 1:8

- 6.5-300 Weatherby Magnum…….. 1:8

- .270 Winchester…………………….. 1:10

- .270 Winchester Short Magnum. 1:10

- .270 Weatherby Magnum……….. 1:10

- 6.8 SPC…………………. 1:9.5, 1:11, 1:12

- 6.8 Western……………………. 1:7.5, 1:8

- .27 Nosler…………………………….. 1:8.5

- 7×57 Mauser……………… 1:8, 1:9, 1:10

- 7-30 Waters…………………………….. 1:9

- 7mm-08 Remington……………… 1:9.25

- .280 Remington…………………… 1:9.25

- 7×64 Brenneke…………………………. 1:9

- .284 Winchester………………………. 1:9

- 7mm Winchester Short Magnum 1:9.5

- 7mm Weatherby Magnum 1:9.25, 1:10

- .28 Nosler……………………………….. 1:9

- 7mm PRC………………………………… 1:8

- 7mm Remington Ultra Magnum 1:9.25

- 7mm STW…………………… 1:9.25, 1:10

- .30 Carbine……………………………. 1:16

- .30-30 WCF……………………………. 1:12

- .30 T/C………………………………….. 1:10

- .30/40 Krag……………………………. 1:10

- .308 Winchester…………….. 1:10, 1:12

- .300 Savage……………………………. 1:10

- .30-’06 Springfield…………………… 1:10

- .30 Nosler……………………………… 1:10

- .300 Winchester Magnum……….. 1:10

- .300 Winchester Short Magnum. 1:10

- .300 Remington Ultra Magnum… 1:10

- .300 Weatherby Magnum……….. 1:10

- .30-378 Weatherby Magnum…… 1:10

- .300 Holland & Holland Magnum 1:10

- .308 Norma Magnum……………… 1:10

- .300 Remington SAUM……………. 1:10

- .300 PRC………………………………….. 1:8

- .300 Norma……………………………… 1:8

- .303 British…………………………….. 1:10

- 7.62x39mm……………………………. 1:10

- .32 Winchester Special……………. 1:16

- .325 Winchester Short Magnum. 1:10

- 8x57mm Mauser………………….. 1:9.25

- 8mm Remington Magnum……….. 1:10

- 8x68S……………………………………. 1:11

- .338-06 A-Square……………………. 1:10

- .338 Federal…………………………… 1:10

- .338 Winchester Magnum……….. 1:10

- .338 Remington Ultra Magnum… 1:10

- .338/378 Weatherby Magnum…. 1:10

- .340 Weatherby Magnum……….. 1:10

- .33 Winchester ………………………. 1:12

- .338 Lapua………………………………. 1:9

- .35 Remington……………………….. 1:16

- .358 Winchester…………….. 1:14, 1:16

- .35 Whelen……………………. 1:14, 1:16

- .358 Norma Magnum……………… 1:12

- .350 Remington Magnum………… 1:16

- .357 Magnum (rifle) ………………. 1:16

- 9.3x62mm……………………… 1:10, 1:14

- 9.3x64mm……………………………… 1:14

- 9.3x74mmR……………………. 1:10, 1:14

- .375 Holland & Holland Mag 1:12, 1:14

- .375 Ruger…………………………….. 1:12

- .375 Remington Ultra Magnum… 1:12

- .375 Weatherby Magnum……….. 1:12

- .378 Weatherby Magnum.. 1:12, 1:14

- .375 Dakota…………………………… 1:12

- .375 Winchester…………………….. 1:12

- .405 Winchester…………………….. 1:14

- .450/400 3” NE………………………. 1:15

- .404 Jeffery…………………. 1:14, 1:16.5

- .416 Rigby……………………………… 1:14

- .416 Ruger…………………………….. 1:14

- .416 Weatherby Magnum……….. 1:14

- .416 Remington Magnum 1:14, 1:16.5

- .416 Barrett…………………………… 1:11

- .500/416 NE…………………………… 1:14

- .44 Magnum (rifle)………….. 1:20, 1:38

- .444 Marlin……………………………. 1:20

- .45-70 Gov’t…………………………… 1:20

- .458 Winchester Magnum……….. 1:14

- .458 Lott………………………… 1:14, 1:16

- .450 3 ¼” NE………………………….. 1:16

- .450 Rigby……………………………… 1:10

- .458 SOCOM………………….. 1:14, 1:18

- .450 Marlin……………………………. 1:20

- .460 Weatherby Magnum……….. 1:16

- .470 NE…………………………………. 1:21

- .50 BMG………………………………… 1:15

- .500 NE…………………………………. 1:15

- .500 Jeffery……………………………. 1:17

- .505 Gibbs……………………………….. 1:1

So, it’s important to know what the twist rate of your barrel so you can choose the proper ammunition for your gun. There’s an easy way to observe or verify the twist rate of your barrel. Using a cleaning rod, affix a tight patch and get it started down the bore. With a magic marker make a small mark at the base of the rod at the top, and another one where it meets the breech (or the muzzle in the case of a lever gun, slide, etc.). Push the rod down the bore until the mark makes one complete revolution, and make another mark at the same reference point (breech or muzzle). Measure the distance between the marks to determine how many inches it took to make one revolution, and voilà! you’ve got the twist rate.

If you look at some of the long-range bullets, like the Nosler AccuBond Long Range, or some of the Berger offerings, they will indicate the required twist rate needed to stabilize their particular bullet. If you want a bit more information, or should the bullet be marginal for your twist rate, you can consult the Berger website (BergerBullets.com/twist-rate-calculator/) and plug in all of your information. Based upon the Miller Twist Rule (more about that in the exterior ballistics section), the Berger calculator will provide you with the level of stability (or instability) of your particular barrel/cartridge/bullet combination. It’s a very useful tool, which can help you optimize your setup.

The Crown

The final point of the barrel, where the bullet exits, is referred to as the crown. A uniform, even crown is invaluable for good accuracy, as it is the very last thing that your bullet will touch before embarking on its journey through the atmosphere. You’ll need to know about the varying types of crowns and how they affect the flight of the bullet. Looking at the end of your barrel, you may see a simple, rounded end and be able to feel the lands and grooves with the pad of your finger. Or you may see a square-cut, recessed affair, known as a target crown. In any instance, you’ll definitely want to be careful with the crown of your firearm; it plays a very important role in its accuracy. I’ve seen my fair share of well-worn lever-action rifles, which need to be cleaned from the muzzle end, sporting worn or nearly eroded crowns from years of swabbing with a filthy aluminum rod. I’m sure if their owners, who were tough as nails and certainly knew how to shoot those guns, saw us today with our polymer bore guides and ball-bearing-handled, nylon-coated cleaning rods, they’d certainly have a chuckle. However, if they could see the difference in accuracy between a healthy crown and a worn one, they’d have no choice but to admit that our methods preserve rifle accuracy better.

An imperfect crown can be the demise of accuracy. I went mildly insane trying to figure out what was wrong with that .22-250 Remington of mine, as I simply couldn’t figure out why it wouldn’t shoot boat-tail bullets. I mean, I tried factory ammunition, handloads, you name it. Because it is a flat-shooting cartridge, I wanted the 53- and 55-grain boat-tail match bullets to work. My pal Donnie Thorne, better known as Col. Le Frogg, weighed in on the matter, and found the cure in one simple sentence: “Try some flat-base match bullets.”

Long story short, once I switched to flat-base bullets, the rifle was printing 1/3 MOA groups out to 200 yards, which makes up a huge portion of my shots with this rifle, unless the coyotes are posing across the hay lots. The crown of this Ruger rifle is less than perfect, and the escaping gas was being pushed on one side or the other of the exiting boat-tail. Switching to a flat-base bullet improved the accuracy immensely and was not a handicap as far as wind deflection and trajectory were concerned. To be honest, the combination of the imperfect crown and slow twist rate should warrant re-barreling the rifle. But I love the way it handles, so I’ll wait a while until I feel it’s time to do so.

Twist Direction

Most of today’s barrels use a right-hand twist; that is, the bullet is spun in a clockwise motion. However, you can come across a left-hand twist barrel, spinning bullets in a counterclockwise motion, and when the distances get out beyond 500 yards or so, the spin direction of the barrel comes into play. A right-hand twist barrel will cause the bullet to drift a measurable degree to the right when the time of flight increases. Conversely, the opposite is true for a left-hand twist barrel, and these considerations must be accounted for when trying to accurately place your bullets on a distant target. Many of the ballistic calculators incorporate twist direction as one of the parameters for long range dope, so it’s important to know. One glance down your barrel and you can easily verify the direction of twist.

Barrel Construction

Steel has long been the chosen material for barrels. It is rigid enough to withstand the intense pressures generated by modern cartridges, yet flexible enough to allow the bullet down the barrel without cracking or shattering. The two most popular types of steel barrels produced are chrome-moly (a chrome-molybdenum alloy steel) and stainless steel. I’ve had excellent results with both, and I honestly feel that either will make a suitable choice for a barrel. Both give long life and are equally accurate, at least in my experiences. Stainless is a bit less susceptible to rust (though not impervious), and chrome-moly can be a bit lighter, but I own and like both types. More important to me is the construction method used to create the barrel.

Cut Vs. Hammer-Forged Vs. Button-Rifled

Most factory barrels in production today are hammer-forged, cut or button-rifled. All three methods have positive and negative attributes. Personally, I’ve found good and bad in all three types along the way, and as long as a barrel does its job, I’m good with it. The cut barrels are probably the most labor intensive, as the rifling is cut one groove at a time in a reamed bore. Krieger, who made the barrel for my .318 Westley-Richards, makes cut barrels. The button-rifled barrels are made in a similar fashion, in that a drilled bore at less than caliber size is utilized to guide the cutting button down the bore. Button rifling is popular with many custom rifle companies like Shilen, as well as Savage rifles—both of which have an impeccable reputation for accuracy. So, with both cut and button rifling, a smaller-than-caliber hole is drilled through the centerline of the bore, and a tool is used to put the finishing touches on the barrel.

Hammer-forged barrels work in the opposite manner. They start with a barrel blank that gets reamed to a dimension larger than the desired caliber, and then a mandrel that is a perfect mirror of the desired bore dimension is inserted into the reamed hole. At that stage, a series of hammers are used to forcefully mold the steel around the mandrel, so that the resulting bore comes out perfect. Undoubtedly, hammer-forged barrels are both cost-effective and accurate, yet some folks feel that they are the least accurate type of barrel. I’ve had some of the best—and worst—accuracy with a hammer-forged barrel, yet I feel it’s due to the fact that they represent such a large portion of the barrels produced each year.

My Heym Express .404 Jeffery uses a hammer-forged Krupp barrel, and yet it gives sub-MOA accuracy consistently. Likewise, I’ve got a trio of Winchester Model 70s (.300 Win. Mag., .375 H&H and a .416 Remington Magnum) and all have exhibited excellent accuracy, accompanying me on hunts all over the world. Likewise, my favorite revolver, a Ruger Blackhawk in .45 Colt, uses a 7.5-inch hammer-forged barrel that allows me to hit targets as far as I can hold accurately. The hammer-forged method occasionally gets a bad rap because it is associated with mass production, but that’s not fair. Heym rifles, makers of some of the finest safari guns available, make approximately 6,000 hammer-forged barrels annually, but only consume about 2,000 for their own in-house use. The remainder are sold to other fine rifle companies, and I’ve yet to meet a Krupp barrel from Heym that didn’t perform very well.

Down The Rabbit Hole

When the cartridge is fired, the primer sends a shower of sparks into the powder charge, which is burned. The resulting expanding gas creates lots of pressure. This sends the bullet in the path of least resistance: down the barrel. It’s also when things get interesting, as the entire situation changes in an instant. Once the bullet passes the throat and engages the rifling, the torque creates a wave of distortion that causes the barrel to swell just in front of the bullet. The barrel will—although minutely—swell and return to original shape as the bullet passes down the bore. In addition, the barrel will “whip,” as if you were holding a fishing pole in your hand and quickly shook your wrist. Barrel flexure is minimized with a larger diameter barrel of shorter length, but those shapes come at the cost of velocity loss and increased weight. In addition, if your barrel is not free floating, meaning that it is touching the stock at some point, accuracy can be affected.

Like all things in life, there are no absolutes, and I’ve seen rifles with Mannlicher stocks where the stock extended to the muzzle and touched almost all the way exhibit excellent accuracy. Many military rifles such as the M1 Garand or M98 Mauser have stocks that extend much farther than do our common hunting and target rifles. Yet, these have shown some amazing capabilities in competition shooting … in no small part to the men behind the trigger. That aside, I prefer my rifles to have barrels free floated so they can swell and torque and whip without interference. That keeps things as accurate as possible. You can test your rifle’s barrel channel by placing a dollar bill under the barrel, and run it up along the stock toward the receiver as a feeler gauge to see if the stock is touching the barrel at any point. If it is, remove a small amount of material from the barrel channel in order to let the barrel move freely during the shot.

The idea of reducing barrel whip by using a stiffer (larger diameter) barrel isn’t a new one, but it definitely works. It not only dissipates heat better, but reduces the amount of flexure to give a more repeatable result, promoting accuracy. The bull barrel is a staple of the target community, as well as being a popular choice among varmint hunters who must hit distant, tiny targets. However, they are heavy to carry, and can be very unwieldy to shoot offhand. Now, I don’t mind a barrel on the heavier side of things, particularly the semi-bull barrels that make a good blend of portability and stability, but I don’t want a bull barrel on the mountain hunts of the Adirondacks and Catskills, nor do I want one when in the African game fields, where the daily walks are measured in miles. There is a way to get the best of both worlds using a light, rigid, carbon fiber. Starting out with a featherweight steel barrel, carbon fiber is wrapped around it, until it achieves the diameter of a bull barrel approaching one inch or more in diameter. This combination is lightweight like a slim steel barrel, but has the rigidity of a bull barrel. The carbon also dissipates heat very well, and it keeps your barrel cooler, longer.

When a barrel gets too hot, it’ll tend to print a bit higher on the target. This occurs because the steel expands and the bore diameter is slightly reduced, creating a higher pressure and thereby more velocity. Heating your barrel to the point that it is impossible to touch without pulling your hand away is never a good idea, as it will lead to premature barrel wear and throat erosion. Allow things to cool, and a barrel should give nearly a lifetime worth of service.

Harmonics

The manner in which a barrel whips, torques and contorts is referred to as barrel harmonics. The idea of accuracy is simply a set of repeatable barrel harmonics. If you use the centerline of the bore as the baseline for your observations, you would see a wave in which the barrel would rise and fall, equally above and beyond the baseline. The thinner and longer a barrel is, the further from the baseline the barrel will whip. Again, a short, thick barrel will have a much smaller deviation from the baseline. Accuracy is optimized when harmonics are repeatable, and when the various pressure waves align in such a fashion that the muzzle diameter is kept at a uniform dimension. Um, what? How can the muzzle diameter change? Allow me to explain a complicated theory in simple terms.

I ran across a theory, presented by radio communications engineer Chris Long, which makes a whole lot of sense and explains some ideas I knew to be true, but had no idea how to nail down scientifically. It also changed the way I look at my own handloaded ammunition. Long purports that a series of crossing waves can, will and do have a great effect on the barrel and its ability to produce a repeatable point of impact (known to us as a tight group). While I am not a scientist (cue Star Trek music: “Dammit Jim, I’m a surveyor not an engineer!”), Long’s theory boils down to this: the ignition of the powder charge creates pressure that sends a shockwave down the barrel, to the muzzle and back again, in a repeating fashion much like the plucking of a guitar string. This ignition stress shockwave can and will move the steel enough to cause a distortion in the bore diameter.

Subsequently, when the bullet engages the rifling, a second force—the swelling of the barrel ahead of the bullet—starts to travel toward the muzzle. According to Long’s sound theory, if those two waves collide when the first wave is affecting the muzzle, the groups will open up as if the crown were out of round, much like my .22-250 Remington was behaving. If you can find the load with which the two waves are separated, the group size will indeed shrink.

Now, there are many variables in Long’s equation, including the amount of powder and the load density, as well as the seating depth of the bullet, and while this isn’t a book on reloading ammunition, this theory makes perfect sense to me as a handloader. It can easily explain how changing the powder charge a mere 0.1 or 0.2 grains would so dramatically affect group size, as I’ve seen for decades in my own handloaded ammo. In addition, the Chris Long theory also explains why some barrels like a particular brand of ammunition, yet others can’t get it to work at all. I think it also explains the drastic changes in group size that can occur when changing seating depth and cartridge overall length. (Which incidentally has been a little trick of mine for years, though I didn’t understand exactly why it worked, I just knew that it did.) The variations in seating depth will definitely affect the barrel harmonics and their timing.

Barrel Length And Its Effects

For years, it was a common assumption that longer barrels were more accurate than shorter ones. It’s an arguable point, but I’ve seen evidence that points to the fact that both can be equally accurate. I do believe that when discussing iron-sighted guns, a longer sighting radius will usually result in an ability to place the shot better, but in a scientific world—say using a machine rest—I’m not certain that the longer barrel will always come out on top.

There is a definite increase in velocity when using a longer barrel, as the longer pipe will build more pressure. The generally accepted velocity loss/gain when comparing barrel lengths is 25 fps per 1 inch of barrel length. While I’ve never had the opportunity to actually measure the velocity loss of one particular barrel by cutting off an inch at a time, I’ve seen studies where this test was performed and that rule was more or less proven. For example, my 6.5-284 Norma is a popular choice among F-Class shooters, and many of those rifles take advantage of the case capacity by using a barrel length of 28 or even 30 inches. My own Savage Model 116 with a 25-inch barrel doesn’t quite match some of the advertised velocities because of the shorter tube, and I’m OK with that. It’s a hunting rifle, and while I normally don’t mind longer barrels, toting a 28-inch barrel through the woods and fields seems a bit excessive to me. So, when I ordered the rifle, I figured the 25-inch length would make a good balance of velocity and portability. The choice is ultimately up to you, whether you want a compact rifle for ease of carry, or the long barrel for additional velocity, but it’s important to know that the measured velocity of Brand X ammunition in your gun may not equal advertised velocities due to the difference in the test gun’s barrel length and the length of your barrel.

When I first started to handload ammunition, I didn’t understand why a particular load prescribed by the reloading manual didn’t obtain the velocity shown in the data. I followed the recipe exactly. Used the test data’s primer, powder charge, case, and bullet and seating depth. But I was still 125 fps below the manual. Then I glanced at the test rifle information. This company had used a universal receiver and a 26-inch barrel to arrive at their data, and my rifle sported a 22-inch barrel. Barrel length was the factor.

Pistol barrels can and will have a similar effect on the performance of ammunition. Many of the micro-carry, or pocket pistols, give lower velocities than their full-sized counterparts due to the decreased barrel length. Ammunition companies have made an effort to optimize the cartridges for best performance in the shorter barrels. Federal Premium HST ammo has a “Micro” line that is designed to function properly in the shorter barrels of concealed carry pistols, and it works very well. My own carry gun—a Smith & Wesson Model 36 in .38 Special—has the 17/8-inch snubnose barrel and, while the velocities certainly aren’t what you’d get from a 4- or 6-inch target gun, I knew that when I purchased it.

These are things to keep in mind when purchasing a rifle or pistol. Does a .308 Winchester need a 26-inch barrel? Probably not, because the case capacity can be utilized in a 20- or 22-inch barrel, and if it’s made properly, should offer fine accuracy. Can you get the most from a 7mm Remington Magnum with a 22-inch pipe? Not likely. This is an example of a cartridge needing a bit more barrel length to achieve optimum results, due to the increased case capacity. Will a short-barreled handgun be as accurate as a longer barreled one? Maybe, but it has more to do with balance and the ability to aim the firearm than actual function of the barrel and its length. Will a 20-inch barreled Winchester 94 carbine, in .30-30 WCF, perform as well as the 26-inch octagon-barreled rifle of your grandfather’s era? For the distances at which a .30-30 is most commonly shot, I’d vote yes, but again, that longer sighting radius of the bigger rifle may cause it to appear more accurate than the carbine, so it would take a machine rest to verify the results. For a hunting application, either is more than acceptable if you practice diligently with an iron-sighted gun (which seems to be a lost art these days), so if you appreciate the compact design of the carbine, have at it.

Editor’s Note: This article is an excerpt of Gun Digest’s The Ballistics Handbook.

Raise Your Firearms IQ:

Next Step: Get your FREE Printable Target Pack

Enhance your shooting precision with our 62 MOA Targets, perfect for rifles and handguns. Crafted in collaboration with Storm Tactical for accuracy and versatility.

Subscribe to the Gun Digest email newsletter and get your downloadable target pack sent straight to your inbox. Stay updated with the latest firearms info in the industry.